Credit: Photo by Giuseppe Enrie, 1931, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Source: Biblical Archaeology Review

Today many consider the Shroud of Turin—the alleged burial cloth of Jesus of Nazareth—to be the most important relic of Christianity.1 It is a linen sheet measuring about 14.5 by 3.5 feet and featuring a monochromatic image on the front and back of a naked male figure. This figure appears to bear marks from flagellation and crucifixion as well as various red spots corresponding to the blows. The human image is the result of a change in the color of the linen fibers, but it remains to be fully understood how such coloration occurred. Two scorch marks, which appear as black lines, and a series of vaguely triangular holes caused by burns, run lengthwise down the fabric, on either side of the human figure. This damage is believed to have occurred due to fire in 1532.

The Shroud was first photographed in 1898, and this year is commonly considered to mark the emergence of sindonology (from the Greek word sindōn, used in the Gospels to define Jesus’s burial cloth), that is, the science—or, rather, set of scientific disciplines—that set out to prove the authenticity of the Shroud. Over the past 120 years, sindonology has produced hundreds of books and articles dedicated to the relic, involving every possible field: chemistry, physics, forensic medicine, palynology, numismatics, and so on. Although the field is dominated by the so-called hard sciences, some authors have also dealt with the relic’s history. These accounts recount what can be inferred from historical documents. But because such are only available from the Middle Ages onwards, historians often use imagination to fill the large chronological gap between the first and 14th centuries. It is telling to see how the historiography of the Shroud during the early modern era and until the turn of the 20th century strove to remove any untoward aspects from its history by suppressing inconvenient documents and creating new legends.

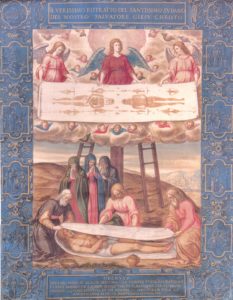

Deposition of Christ (1620), by Giovanni Battista della Rovere, portrays the imagined origins of the Shroud of Turin. It shows Nicodemus, Joseph of Arimathea, and John the Evangelist wrapping Jesus’s body in a burial cloth. The angels above display the resulting image.

Credit: Galleria Sabauda, Turin

There are two irreconcilable positions on the authenticity of the Shroud: The camp of sindonologists assert the relic’s authenticity, and the other side insists the Shroud is a pious medieval forgery. The overwhelming majority of scholars has supported the latter view, while the former has always enjoyed support in religious circles as well as a great deal of coverage by media outlets, always hungry to report on the supernatural and mysterious.

Thanks to the tenacity of sindonologists, the Shroud has survived even the most severe blows that brought down the structure of a belief in its authenticity. Historically, the first substantial blow came at the end of the 19th century, when prominent French historian and canon Ulysse Chevalier published and commented on the medieval documents referring to the moment the relic surfaced in the historical record. In particular, Chevalier reported on the position expressed by two contemporary bishops of the city of Troyes, the diocese in which the relic appeared in the 14th century, who denounced the relic as a forgery and forbade people from venerating it as the real shroud of Christ. Another critical assessment of the Shroud came from archaeological studies of the type of cloth and Jewish burial practices used at the time of Jesus that suggested the relic was from the Middle Ages.

The most serious blow then came from modern scientific analysis of the artifact. The radiocarbon dating of the fabric carried out in 1988 in three different laboratories indicated a date range of between 1260 and 1390. As is well known, this evidence failed to convince the Shroud’s supporters, who continue to produce literature to the contrary, discrediting the radiocarbon results on a variety of grounds. Meanwhile, the Catholic Church has not allowed any new scientific examination of the cloth, alleged human blood, or the nature of the image.

Understandably, the authenticity discussion has almost completely stalled out. With no new data to consider and the two camps entrenched in their positions, is there anything left to say about the Shroud? If we do not want to engage in the fight over its authenticity, is the Shroud still an object deserving of further study?

We need to recognize that the issue of authenticity is only one among many. As a professional historian born in Turin and familiar with the Shroud from childhood, I felt very uneasy when I reviewed the extant scholarship on the subject and realized that very little had been published on the relic’s history and archaeology. This is due in part to the fact that professional historians and archaeologists—most of whom consider the Shroud to be a medieval artifact—prefer to keep their distance from such a controversial subject. As a result, the Shroud is absent from history textbooks and studies of ancient or medieval Christianity or Christian archaeology. It remains a disputed object that scholars prefer to ignore. Most books on the Shroud either have copied from each other or are shaped by devotional interests. Their authors usually lack sufficient training in historical-critical methods, and their coverage of historical and archaeological aspects is insufficient.

It was in this spirit that I set out to investigate the historical and archaeological sources, devoting approximately a decade to the study of the Shroud. In my research, I considered both published sources and unpublished documents from public and private Italian, Vatican, and French archives.2

Although knowing the origin of a relic is certainly important, it would be a mistake to focus all efforts on this point. The issue of origin and authenticity is only one among many. Cynically speaking, most relics are intrinsically worthless objects—materially, the Shroud is nothing but an old piece of cloth. Relics only gain importance when someone attributes it to them. It would also be a mistake to focus on a single relic. Expanding the focus beyond one particular object to examine also all that surrounds it has the potential to highlight the power of symbolic language and to understand the historical underpinnings and meanings.

The Veil of Veronica is one of the multiple shrouds and veils historically associated with Jesus’s execution and burial. This painting by Lorenzo Costa is titled Saint Veronica (1508).

Credit: Shonagon, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

On the latter point, it is important to note that until the second half of the sixth century, no one had ever looked for Jesus’s burial cloths, and that there was no record of them. It was only in the sixth century that burial cloths began to appear among the references to various relics of Christ. It is very instructive to follow the stories of these “sister” shrouds, which increased in number over time. They came, one by one, from Palestine and entered collections in all the most important cities of the world. Since the Carolingian period (eighth to ninth centuries), France has stood out as the place with the highest concentration of shrouds. Although some of them vanished, others still exist: The shroud of Cadouin was venerated until 1933, when it was proved to be a medieval Islamic cloth; or the shroud of Carcassonne, also from the Middle Ages. In Spain, the shroud of Oviedo is still regarded as a relic despite its dating from approximately the eighth century.

Among the dozens of alleged shrouds and sudaria (or, small cloths), the Shroud of Turin is unique because it, unlike the others, bears the image of Jesus’s tortured body. There were cloth relics with the image of Jesus already in late antiquity, but those depicted only his face: the Veil of Veronica, Mandylion of Edessa,3 and the Camouliana.

My recent study of historical documents corrects a great many misconceptions about the Shroud of Turin and provides a clear description of the first decades of life of this cloth, which appeared practically out of nowhere around 1355, in a country church in the middle of France. At the time, ecclesiastics, bishops, nobles, and even the king of France and the Pope all took interest in the matter.

Since the 16th century, the Shroud of Turin has been a powerful religious relic and political tool. This photo is of the 1933 exhibition of the Shroud in the Cathedral of Turin. Credit: Archivio Arcivescovile di Torino

When it first appeared, two local bishops declared it to be a forgery, the king of France tried to seize it, and the pontiff forbade people from describing it as the authentic linen cloth that once enveloped Jesus in the tomb. However, matters took a different turn in 1453, when, after a series of events worthy of a historical novel, the Duke of Savoy illegally purchased the Shroud, invalidating all previous acts of censorship. When it was transferred to Chambéry and then, in 1578, to Turin—the two capitals of the Duchy of Savoy that later became the Kingdom of Italy—the relic became the most precious religious object of the sovereign family. It also played a political role in the hands of the House of Savoy.

Following the history of the Shroud means touching on multiple themes related to theology, devotion, literature, art history, and politics. The relic may seem frozen in time, but it is not a static artifact; rather, it has very much reflected changing historical circumstances, and its role in history has evolved together with societal changes. It first had to face the criticism of the Protestant world, then that of the Enlightenment, then critiques from modern historians and scientists, and finally—after the authentic documents had surfaced and opposition to the relic even by prominent ecclesiastics—the disaffection of those who had come to view the cult of relics as nothing but the survival of old superstitions. Yet, through waxing and waning fortune, the Shroud has survived to this day.

About the Author

Andrea Nicolotti is Professor of History of Christianity and the Churches at the University of Turin. A leading specialist on the history of relics and shrouds, he has published two books on the subject in English: From the Mandylion of Edessa to the Shroud of Turin: The Metamorphosis and Manipulation of a Legend (Leiden: Brill, 2014) and The Shroud of Turin: The History and Legends of the World’s Most Famous Relic (Waco: Baylor Univ. Press, 2020).

Notes:

1. This article discusses how the Shroud of Turin has been viewed, studied, and interpreted throughout history and does not present arguments for or against its authenticity.

2. I presented the results of this investigation in my book The Shroud of Turin: The History and Legends of the World’s Most Famous Relic (Baylor Univ. Press, 2019). Art historians, in their turn, may examine the Shroud in the context of the artistic culture of early modern Italy: Andrew R. Casper, An Artful Relic: The Shroud of Turin in Baroque Italy (Penn State Univ. Press, 2021).

3. See Strata, “Is This the Face of Jesus?” BAR, July/August 2011.